I think we can all agree that parenting has gotten tougher in 2020. Life is uncertain, and the demands on parents increased ten-fold with trying to work from home, while helping your kids with online school and generally just trying to make it through the COVID-19 pandemic.

With all this going on, is it any wonder that our beautiful, charming little ones can turn into meltdown monsters at the drop of a hat?

Our kids are dealing with the typical developmental tasks, such as learning to understand and express emotions, self-regulation and self-advocacy, but in the current climate, they are also dealing with huge disruptions in their everyday lives, parental stress and loss. Anxiety and worry in children can be expressed in ways that differ significantly from adults. Signs may include:

- finding it hard to concentrate

- not sleeping, or waking in the night with bad dreams

- not eating properly

- quickly getting angry or irritable, and being out of control during outbursts

- constantly worrying or having negative thoughts

- feeling tense and fidgety, or using the toilet often

- always crying

- being clingy all the time (when other children are ok)

- complaining of tummy aches and feeling unwell

(more information here)

Based on the list above, our kids’ anxiety about loved ones getting ill, lack of social interaction and connection with schools closing down for social distancing and so on, can easily be expressed through tantrums, meltdowns, crying and anger.

With the amount of things our kids are dealing with, it is safe to say that self-regulation should take a back seat for the moment. Our toddlers, primary schoolers and even high schoolers need us more than ever to help them regulate, which is where co-regulation comes in. The science shows that effective development of emotional self-regulation is mediated through connections with reliable caregivers who provide a safe, soothing space where regulation is modeled. The science shows that repeated cycles of emotional dysregulation, followed by soothing, relaxing intervention from their caregivers build a foundation of safety and trust (Fahlberg, 1991; Cozolino, 2006). With the repetition of this cycle, children learn the expectation of the soothing response, which forms the foundation of self-regulation.

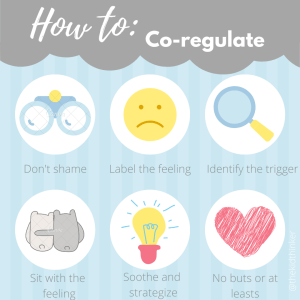

So, how do we co-regulate with toddlers, children and teens?

Step 1: Don’t shame

Our children may seem beyond the age of needing to be rocked, and soothed in a warm loving way, and our first response to their emotions and outbursts is often punitive. Imagine your child coming in the room, slamming doors or throwing toys – what is your first response? Protesting against their behaviour, yelling, docking privileges? We expect toddlers to teens to be able to self-regulate, often failing to take into account that they still experience overwhelm and need a helping hand.

It is easy to react to the behaviour and fail to take into account the emotion entirely. We are easily influenced by our children’s behaviour and often look for quick fixes to stop it in its tracks. But when we intentionally look past the behaviour and search for the emotion behind it, we realise that our children are people too. Take a second to become present and aware of your own emotional response and then extend this awareness to your child – approach them with compassion, rather than shaming their behaviour.

Step 2: Label the feeling

Younger kids tend to lack the vocabulary to express their emotions clearly, while older kids just don’t have the practice of checking in with the feelings and naming them in the moment. This is where you come in. In a soft, warm tone, label the feeling for your child. This can sound like “you are having a big feeling right now. It looks like anger” for younger kids. For older kids, this might sound like “it looks like you are very upset right now”, bearing in mind to use age appropriate labels. Once you identify the feeling, be careful to validate it – we often tend to brush off these emotions as being “trivial”, but in the moment, this is a very real, very serious emotion for your child. Listening to their small things when they are young, sets the stage for them to talk about the big things when they get older.

Step 3: Identify the trigger

Our kids may not yet be able to make the connection between the trigger and their response, so identifying the trigger could be very helpful, and models how to talk about their feelings. For our older kids, asking them about what happened might be helpful – be careful however, to ensure that your tone conveys concern rather than condemnation. Sounding exasperated or bored might send the wrong signal. When we express true concern, our children trust us to be a safe holding space for their emotions

Step 4: Sit with it

It seems counter-intuitive, but co-regulation, and the development of subsequent self-regulation requires us as the adults to set aside our typical responses to inappropriate expressions of anger. By setting aside our inclination to stop the behaviour or pacify the child, we teach our children that emotions are safe, and that they are valid. To co-regulate effectively, our goal is to absorb some of the pain, hurt, or anger. This is a gift to our child, one in which we demonstrate the self-restraint they need. It is okay to let them work out all this emotion before peppering them with questions, alternatives or strategies. Be there while they do this, and be present. When we become distracted by our phone or a task, we unwittingly send the message that their emotions are not as important as whatever else is going on. Speak to them in a warm, soothing tone of voice, and if they can tolerate it, pair it with physical soothing as well. Sometimes, talking can exacerbate the situation, be aware of when this is the case, and sit with them in silence.

If your child is at risk of hurting himself or others by hitting or throwing things, for example, you can set boundaries. This may sound like “I know you are angry, but I can’t let you hit.” At times, a verbal boundary may be enough, but a physical one may be needed if the dangerous behaviour continues. You could say something like “I can’t let you hit your sister, so I am going to stand between you”

Step 5: Soothe and strategize

Once your child is calmer, and able to converse, begin talking about what is going on and some things they can try to calm all the way down. Modeling is your best friend here – if breathing is a strategy you work on, tell them to breathe with you, and then show them how to do it. Other self-regulation strategies may include: heavy work (such as cleaning or sweeping), deep pressure (such as bear hugs, or jumping on the trampoline) or repetitive activities (such as beading, listening to music). Work on finding strategies that are effective for your child, bearing in mind that different activities or strategies work better for different emotions. This is a collaboration, however, so talk to your child about what might help them calm all the way down. This can sound like “What can we do to help you feel all the way better?” or “Should we try (option) or (option) to calm all the way down?

Step 6: No ifs, ands or buts

This last step is where so many parents fall off the wagon. By adding a clause or caveat using “but” or at least, we invalidate their feelings. Instead, acknowledge their feelings all the way through, without adding a clause. For example, you could say “I know you like to play. You don’t want to pack away right now” instead of “I know you like to play but its time to eat.”

Keep narrating and acknowledging their feelings, rather than trying to make it better or getting them to focus on the positive by using “at least.” Distraction from the real upset teaches our kids that their feelings aren’t meaningful. Be aware of your own tendency to want to pacify (you are human, after all!) and focus on helping them to feel seen and heard.

Many years ago, I worked with a student of about 9 years old, and let me tell you, he had BIG feelings about things. He had a language delay, and one of the most valuable skills we taught him was to label how he was feeling. Just feeling heard and understood halved the intensity of the behaviour. It took time, but over the course of a month or so, he was able to let us know what was going on before he had a meltdown, and we could jump in to help him without incident.

By acknowledging the humanness of our children, without expecting them to hide or suppress any part of it for the sake of our comfort and convenience, we do so much more for our children’s ability to self-regulate and cope with adverse situations. This is the ultimate goal of parenting with intention.

Below are some of the books that have saved my sanity over the years! I hope you find them as helpful as I have: