How often do you hear yourself saying “I’m counting to three and this better get done!” or yelling “go to your room and think about what you’ve done!” or at worst, finding yourself hitting your child?

Many of us, myself included, come from a cultural background where our parents believe(d) that punishment is not only a way to improve their children’s behavior, but also a hallmark of being a good parent. South Africa has passed a law prohibiting parents from hitting, smacking, or otherwise physically punishing their children as recently as September 2019, declaring it to be unconstitutional. They cite the following:

“The vulnerability of children, their rights to dignity and to have the paramountcy of their best interests upheld, as well as the availability of less restrictive means to achieve discipline, render moderate and reasonable chastisement unconstitutional.”

Constitutional Court

While this addresses corporal punishment, with which I am in whole-hearted agreement, it fails to consider other forms of either positive or negative punishment that parents now find themselves employing. These measures can include yelling (+), time-out (-), loss of privileges (-) or in extreme cases, being kicked out or locked inside the house (-).

“Spare the rod, spoil the child” was often quoted to me when I questioned why punishment was even necessary. And this outmoded way of thinking survives to this day, and yet parents will punish, and see limited or short-term change in their children’s behavior. The reason for this is simple. Punishment is ineffective. Here is why:

- Punishment does not teach the missing skill

As parents, the temptation to punish is a strong one. This is for two reasons. Firstly, the behavior stops almost immediately, which we at an intellectual level perceive to be the goal. Secondly, our frustration and sense of shame because “If I were a good parent, my child wouldn’t behave in this manner” is immediately reduced because we enacted the role of a “good parent.”

What this fails to consider is the fact that misbehavior, or challenging behavior is often the result of some missing skill. If children could do better, they would. If your child has a tough time cleaning up after themselves, the missing skill could be planning or organization. A simpler missing link could be that their standards of cleanliness is simply not the same as ours. If a child is aggressive, they are likely missing social, communication or executive functioning skills which allows them to inhibit the desire to hit, communicate appropriately, or understand the other person’s point of view.

If we only punish the behavior, but fail to teach the missing skills, we are simply putting out fires instead of catching the arsonist. We end up having to keep on putting out fires all the time. I am sure you have heard that discipline means to teach, rather than to correct, and the adage stands. If we want our children to behave better, we need to teach them what “better” is.

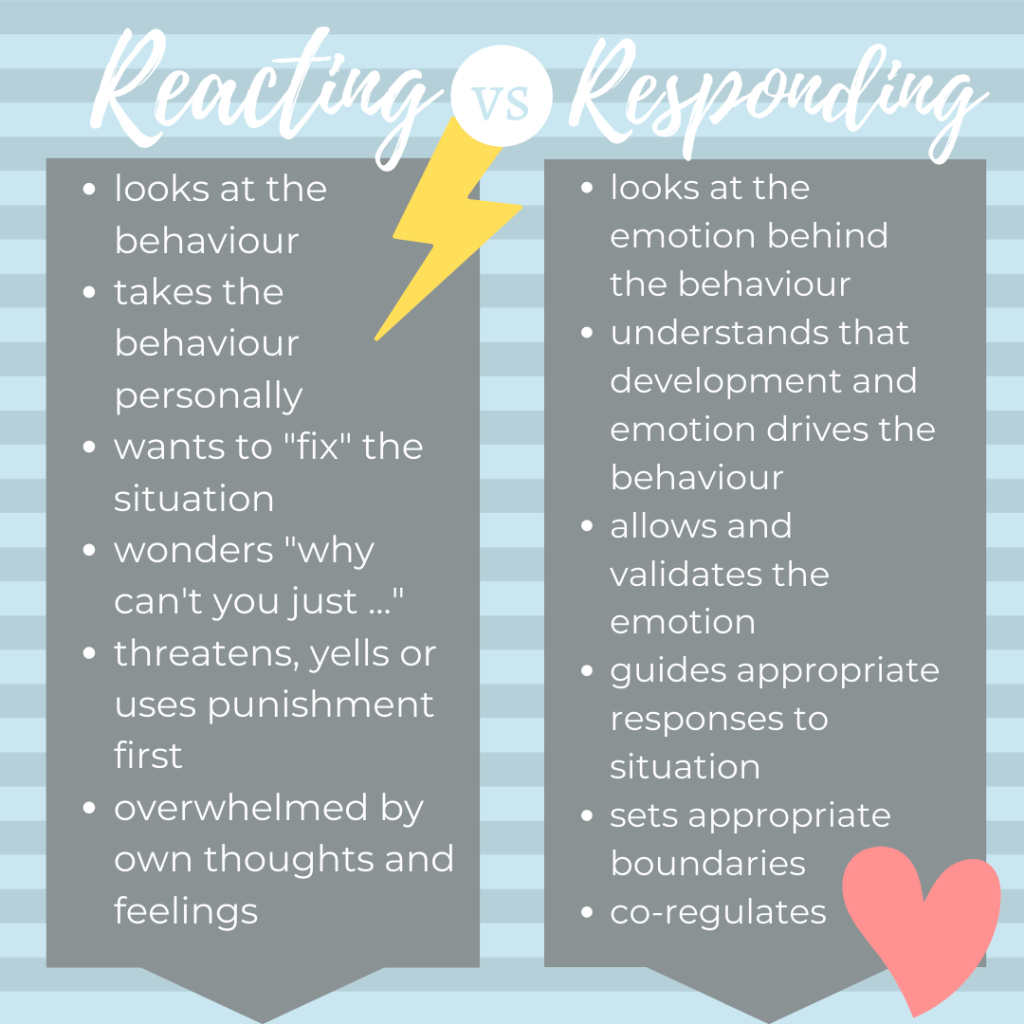

- It is reactive, and often emotion driven

I touched on this briefly in the above point, but it warrants its own paragraph. Punishment is about us and how we feel about what is happening. When our child is misbehaving, we might feel triggered, which results in a whole host of unpleasant feelings, especially if we have addressed the issue recently. Another thing that might be happening is the “good parent” message playing on a loop inside our heads. This message differs from person to person, depending on their milieu, but can sound like “I must be a bad parent, look how he is behaving!” or “If I don’t punish this, I am being permissive.” These thoughts and feelings can result in feelings of overwhelm, which results in our rational, thinking brains shutting off and putting the co-pilot, our emotional brains in the driver’s seat. When we react emotionally, it is often on the fly, and without regard for the long-term outcome. And more often than not, it leaves us with an emotional hangover, such as guilt and shame.

- Punishment diminishes the whole child, not just the behavior

Children are not able to put the blame where it belongs. They do not experience punishment as “oh, mom is just punishing hair pulling behavior, because hair pulling is bad.” Instead, they experience it as “mom is punishing me, because I am bad.” When we punish our children, for whatever reason and in whichever manner, they interpret our response to their behavior as the way we view them. This can have far-reaching consequences for their self-esteem if they are internalizing the message that they are bad.

They are intellectually and emotionally unable at a young age to recognize what is being punished and see it as they are being punished. This can create shame, which as Brené Brown defines it in this post, is the intensely painful feeling that they are flawed (not their behavior), and thus unworthy of love and belonging.

Taking our children’s perspective, and perhaps through reliving some of the moments in which we were punished as children can be painful, but it does help us to see that the way children interpret punishment can diminish them as a whole. Ultimately, punishment changes the person they become, and often not in a healthy way.

- Punishment provides external motivation, rather than internal motivation to improve

Punitive parenting practices often result in short- or medium-term change in the behavior, but often fails to have long-lasting effects. This is because the drive to change the behavior comes from an outside force. Children are motivated to avoid punishment, rather than motivated, or self-disciplined to improve the behavior.

Instead, they learn how to avoid it. This can result in our children learning one of two (or both) things to avoid punishment. Firstly, some children are prone to becoming approval addicts, and internalize the message that they need to be perfect in order to be worthy of love and belonging. Adult versions of this mindset include co-dependency, doormats, and perfectionists. The second is that they learn to lie or sneak around, avoiding getting caught doing the behavior in order to escape punishment. Regardless of the mindset that develops, the outcome is the same – neither child learns the self-discipline required to keep them moving forward in healthy, respectful ways.

It is important, however, to recognize that we are human and that we are going to mess up and react instead of responding to our children’s behavior from time to time. Do not beat yourself up about it but do make a point of making it right with your child.

True discipline

Although there are many paradigms and frameworks out there for parenting without punishment, they share some core features, namely respecting the dignity of the child, and being kind but firm.

When we incorporate this into our personal and parenting values, we find ourselves responding instead of reacting. But I know you are here for tips instead of a lecture, so here are my favorite tools for disciplining without punishment:

- Know where the behavior is coming from

When you see the root of where the behavior is coming from, such as seeking attention, needing to have control, seeking revenge or assuming inadequacy, you are better able to “catch the arsonist.” When you catch the arsonist, you are addressing the root concern and avoid feeding into the behavior.

- Have a plan

When you have a plan for how you are going to respond when you see the arsonist, you are less likely to go into the “punish or perish” mode. Crafting your plan should address:

- Finding the arsonist

- How to avoid feeding into the behavior

- Setting and holding the boundary

- Teaching the appropriate skill

Bear in mind that teaching in the moment might not always be the best time to discipline, especially if you are feeling triggered, or your child just is not in a space to be able to hear the teaching. Some cool-down time might be necessary before addressing it. Another benefit to cooling down first, is that you can create a calm, safe space in which to role-play and practice the positive opposite, or alternative, behavior.

- Stick with the plan

If you falter and lose confidence midway through, keep in mind that you created this plan for moments exactly like this. Follow through. Remember that if you give up (or in) at this point, your little one is going to feel unsafe. Remember that setting and holding a boundary makes you safe, and predictable and lets your child know that you are the leader and that you will be there to catch them if they fall. If you lose confidence, this can increase their anxiety because if you are not leading, then who is?

Check out my bookshelf (below) for books to help you create your plan or contact me to book a session!

On My Bookshelf …

Below are some of the books I used to create this post, and that have so many great tools to help you use conscious discipline, or positive discipline: