Seared in my memory is the image of a three-year-old, valiantly refusing to put a bite of food in their mouth. The harder we pushed, the more he refused. And this was something he had eaten the day before! An eternity later, after much coaxing and prompting, he ate. And neither of us felt good about it. Power struggles can come in all shapes and sizes. They might look like a battle of wills over what your child is willing to eat, wear, or do. Alternatively, it might look like back talk, ignoring requests, not doing homework or simple refusal to follow instructions the first time you ask. The one thing they do seem to have in common, is frustration at the sense of not being able to get them to do what you want. This can start in the toddler years, and without careful examination, can last well into the teen years, leaving both parent and child fed up, frustrated, and feeling discouraged. Before we can successfully side-step power struggles, there are a few things we need to unpack around, and about power struggles.

The anatomy of a power struggle

Power struggles follow a reliable pattern, which helps us to predict and sidestep them. Here’s a breakdown of a typical power struggle:

- A request or rule is made

- The child refuses passively (by ignoring) or actively (by vocally or physically resisting)

- The request is repeated, often with greater intensity

- The refusal continues

- The parent decides that they need to “win” and presses harder, either by raising their voice, coaxing, or coercing through threat of punishment

- The child decides “you can’t make me” and digs their heels in deeper.

- Lather, rinse, repeat

You are both strung out on power, high on control. And the come down is HARD. What we need to understand is that, as humans, we have physiological reactions to being told what to do. Somewhere, between the message leaving our mouths and reaching their brain, a little message crept in – “resist.” This is true for each and every one of us.

Children want autonomy

From the time that our children are able to explore their environment with some independence, they are aiming for one thing – autonomy. As Erikson posits in his theory of the psychosocial stages of development, between the ages of 18 months and 3 years, children enter an age where they begin seeking a sense of personal control. The cost of not attaining this sense of personal control. Shame and doubt. If children are not allowed to exercise healthy control during this stage, they may become over-reliant on others, lack self-esteem, or feel a sense of shame or doubt about their abilities.

Being able to make decisions about what they do, where they go, and what they play with helps children develop confidence in their own ability to survive independently of their parents. While their young brains are still developing, they straddle the line between wanting to be independent, and lacking the experience and judgement to be completely autonomous. This is where parents come in.

When do power struggles become unhealthy?

Power struggles are part of normal child development, but if handled incorrectly, can become problematic, both within the parent-child dynamic as well as in other areas of the child’s functioning.

If allowed to continue unchecked, power struggles can damage the parent-child relationship by creating an atmosphere of disconnection, hostility, resentment, and rebellion. And this is the best-case scenario when a parent and child lock horn, with neither of them backing down.

When a parent prioritized winning over their child, and does so through punitive measures, their children can withdraw, either by relinquishing all power and looking to others for direction in even minor tasks, or by learning to become sneaky.

On the other extreme, when a parent is permissive and avoids power struggles by giving in too much or too often, the child learns that the world is there to serve them. They fail to gain a sense of healthy control over their world by doing things for themselves or following rules that have been set for their benefit.

It takes two to tango

It is impossible to have a power struggle by yourself. Trust me, I’ve tried. The best way to avoid a power struggle then, is to take a step back. We need to check our intent. Are we looking for compliance, or cooperation?

The distinction seems subtle but can make all the difference. Compliance requires the child to wholly submit to the adult’s will. There is no sense of control or assertiveness. Compliance is an “outside in”, “because I said so” approach. While it is nice to be obeyed, we need to be aware of the repercussions of demanding compliance. Children who are compliant are often unable to assert themselves, blindly submitting to the will and requests of others.

Cooperation on the other hand allows the child to learn how to control their actions and decisions to reach a common goal. It invites the child to participate meaningfully, having had the opportunity to exercise autonomy through decision making. Cooperation is an “inside out” approach, and requires the requester to gain the child’s buy-in. It is respectful of the child’s intellect and dignity.

How do we gain cooperation (and avoid a power struggle)?

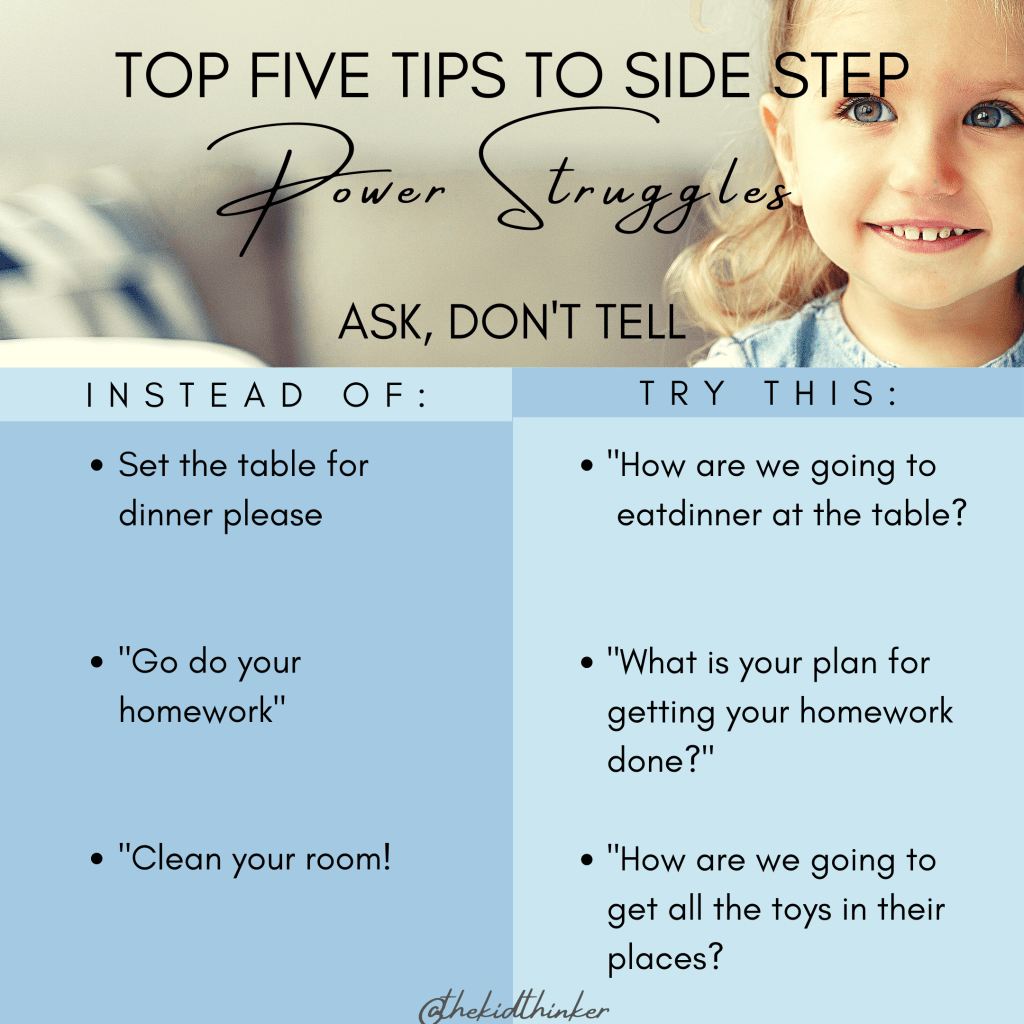

- Ask, don’t tell

Instead of telling them what to do, invite cooperation by asking “what” and “how” questions. Instead of the brain receiving a message of “resist”, being asked a question sends the message “find an answer.” This invites cooperation because they feel good about getting the answer, which builds momentum. Alternatively, ask for help! Children have an inborn drive for altruism, and few can resist helping a parent.

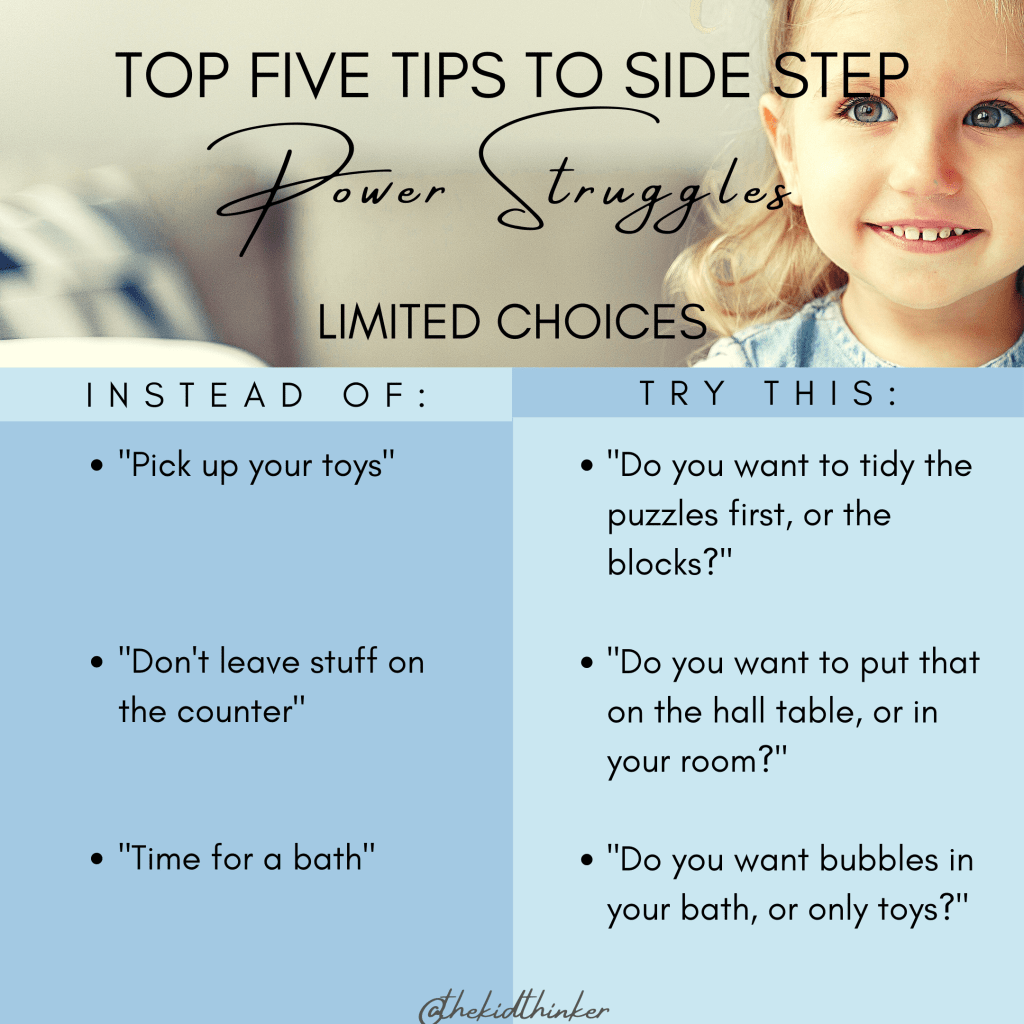

- Provide limited choices

This can be done in several ways. You can make a choice wheel with solutions to typical problems with your little one. Or, when you need them to complete a task, give them a choice about how or when they complete the task, but not what. For example, “do you want to brush your teeth before you put on your pajamas, or after?” or “do you want to tidy the puzzles first, or the blocks?” – this allows a sense of control, in a healthy and measured way, without inviting resistance. If they choose something that is not an option, let them know kindly but firmly, and then restate the options.

- Make it fun

Children are naturally motivated by fun! Think about how you can turn a task into something they would enjoy. Hate getting dressed? Be silly and put the items on yourself. Hate tidying up. Have a race! When we highlight play and humor, children are more likely to participate in an activity because they want in on it.

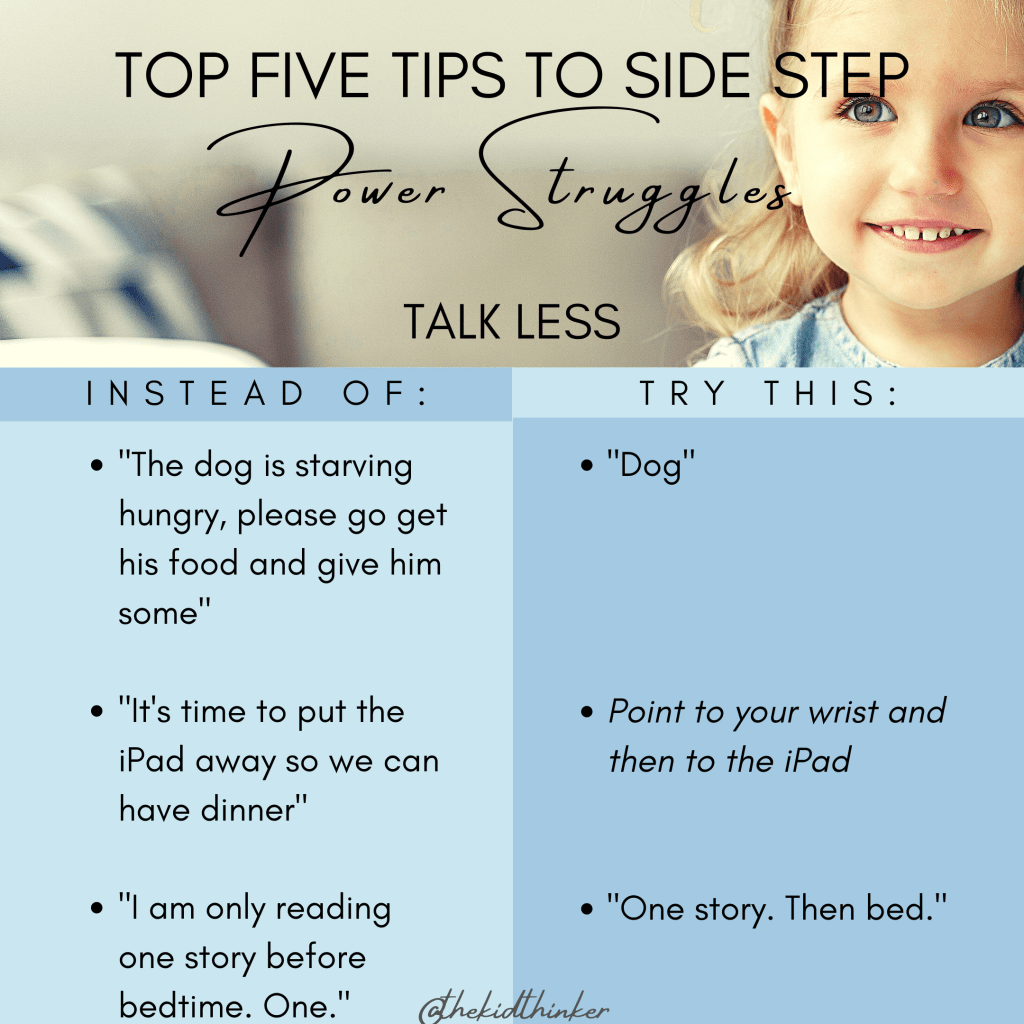

- Talk less

As I’ve mentioned above, you can’t have a power struggle by yourself. By talking less, there is less to argue against. For some kids, this might mean using a non-verbal signal (that you have agreed on beforehand) or using three words or less. Don’t respond to back talk – repeat the request kindly but firmly. Don’t get into the consequences, why’s and wherefores. This invite arguing and resistance. Only say what needs to be done and then stop talking.

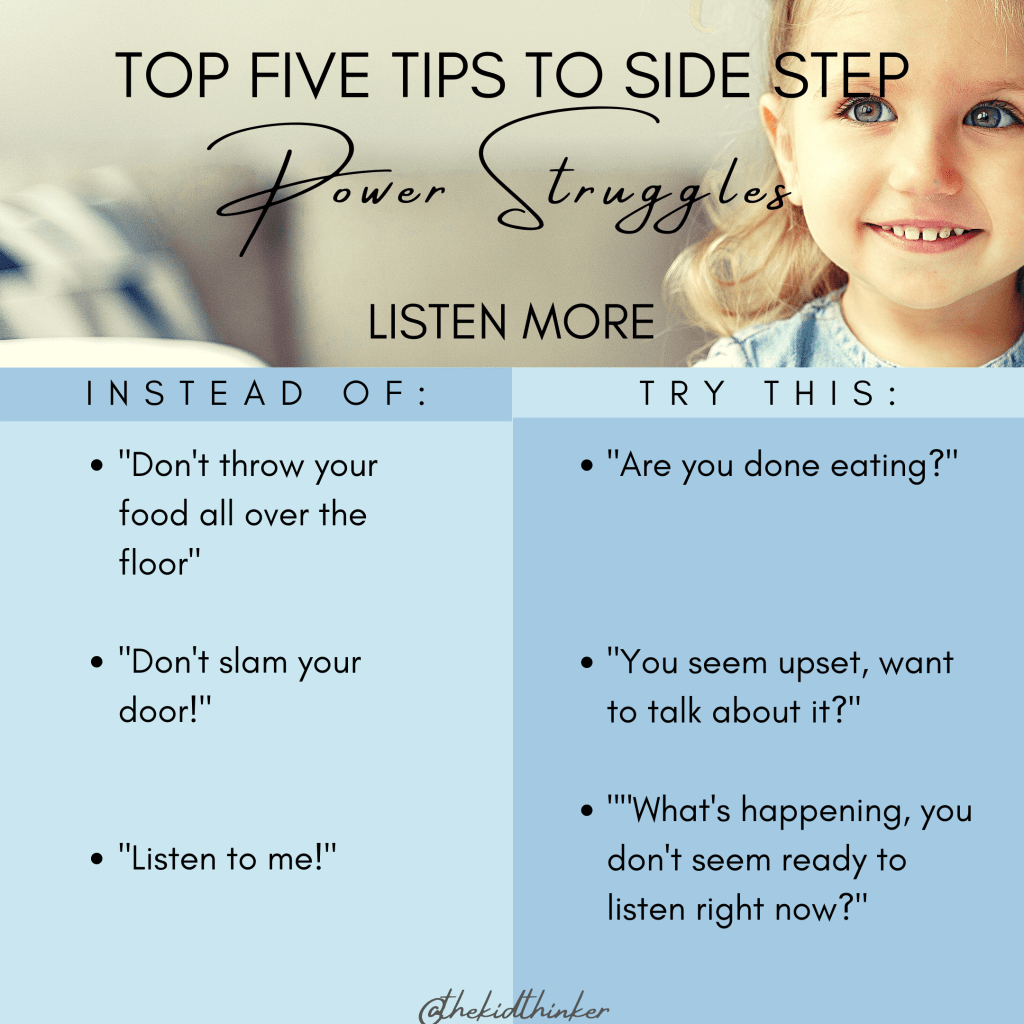

- Listen more

Talk less and listen with the sincere attempt to understand not only what your little one is saying, but what they might mean. Rephrase to clarify understanding. Often, children have very real reasons for not wanting to do something. When we aim to understand, children will return the respect.